The REAL Social Contract

Where is this contract that I never signed? Oh! It's implicit (and hypothetical). Good thing it's not arbitrary such that an accident of my birth binds me to it. Wait? It is. Well then, at least it's not unilateral such that the government is beholden to me and can't change the terms halfway through. Hold on... getting some more information here.... what the fuck?!

In actuality, most if not all states don't derive their actual powers from the consent of the governed. They derive them by chicanery, overt force, creating a birdcage, the tyranny of tradition, and psychological exploits. The consent of the governed is the same as the consent of a mugging victim because he chose to have a lot of money on his person while on the wrong side of the tracks.

Is it better than the natural rights garbage which "the other side" tends to espouse? Sure. But that's a low bar to hurdle. Because people are afraid to own their values and they need to argue to win, they try to find ways to justify positions they didn't reason themselves into. The brain is a pattern-matcher and people are more easily convinced by simple rules than convoluted ones; simply find vague similarities between two things and extrapolate that into a general, metaphorical rule set and viola a convincing but non-factual normative construct is born.

Social contract arguments are incredibly painful to watch. A debater is making a speech. He wants to argue that some person has such-and-such a legal right. Or maybe such-and-such an obligation. But he can't for the life of him think of why. Flash of brilliance: There exists a mythical contract that no one has ever seen or signed, and its terms include exactly the moral stipulation that he's looking to prove.

This approach has its slightly more contorted variations. Maybe the social contract was broken, so the person breaking that contract is going to lose certain legal/moral rights. (Often only loosely connected to the clause 'broken' in the first place.) Or maybe the speaker asserts that the social contract involved some 'trading' of rights, where some pre-civilised caveman gained certain social duties in return for a right not to be clubbed over the head. All these variations are also terrible.

Few top-tier debaters, and virtually no professional political philosophers, would nowadays make or defend the social contract argument as it is used in debating today. Here's why: Social contract arguments are transparently false and intellectually dishonest, even though they are so commonplace in debating that most debaters don't question their basic premises.

People Voluntarily Chose to Join Society

First off, for the most part, no they didn't - at least regarding statist societies. Circumscription theory asserts that some tribes were kicked out of prime land by other societies and then either had to join those societies or try to survive on marginal land. The choice of starving or joining society doesn't sound very voluntary.

Secondly, even if they joined society voluntarily doesn't mean they agree to any formal institutions which may arise afterwards or change through revolution. Society can operate under informal rules without an institutionalized government. It can easily be the case that a government is either formed by those seeking to gain power or it evolves into place without the consent of everyone present.

Thirdly, children don't voluntarily choose which society they are born into. Their choice of parents is a crapshoot.

Fourthly, even if a society with a government came along and allowed others living in a state of Hobbesian anarchy to voluntarily join it, how voluntary is that choice since, if life was "nasty brutish and short," a decision to join would be made under duress?

You Choose to Remain in Society

There are at least two major problems with the claim that remaining is consent:

1. Moving imposes immediate and potentially permanent costs.

Cost expresses values, this is true, but costs can also indicate harm when one is putting you in a situation you otherwise wouldn't have to be in. If the mafia rolled in and began to demand payment from all businesses and residents in town unless those residents left, would it be considered reasonable for those people to pack up instead of making payment so long as it was possible to move somewhere else? Should those people ignore the efforts they placed in building society and interpersonal connections, their shared history and futures, their culture and language and traditions? Worse, what of people born into a society where the mafia already had rule. Does the fact that parents chose to procreate suspecting what their children would endure justify binding the children for the sins of their parents?

Viewing voluntariness as a spectrum rather than a boolean is a saner, more "common sense" approach. States are monopolies or near monopolies and the costs of switching "service providers" is much higher than that of changing internet or phone companies.

2. It's a choice of jailers

Even if someone is willing to give up friends, family, work, culture, and everything else to make the trek to another society, the government claiming jurisdiction in that society will impose often similar rules to that of the state the individual is fleeing. There are certainly some states that are better than others in various areas but, with only around 200 choices, it's unlikely that there is a place which meets with even a majority of what the expatriate is looking for. If, magically, the government is perfect, the society might not be. If both are perfect, the geography might not be.

There are no readily accessible areas which support human life not already under the claim of some state. In fact, when some people tried to make new land, the nearby state claimed it. The choice of being free of some state or to create a new state without displacing another is no longer possible and a relief valve for oppression and the reasonableness of the "love it or leave it" argument has been effectively eliminated.

|

At some point this was bound to happen, but a semblance of voluntariness could be retained if nations were far smaller and had fluid borders - namely if micronation panarchy was the norm. But it's not.

People, at some subtle level, recognize this lack of choice and do what most individuals feeling powerless do - fall into depression, distraction, or believe comforting lies to feel empowered again. The largest of the comforting lies are that government is society and the government is the people because voting works and is a good idea. |

Government is Society / Government is The People

Humans have a disposition to identify with "the team" and "the alpha." The alpha now just happens to be an institution instead of a single individual. Groups who banded together for country had a better chance of conquering the resources used by others as well as protecting their own resources. Strength through unity and all of that. I also think the individual feeling of powerlessness aspect plays here too. It is a comforting belief to think that I am empowered because I have some control over the alpha system and am therefore important. If I can't beat them, I'll join them since the cost of siding with an inferior coalition used to be a thorough beating. Nowhere is the "join 'em" behavior more visible than siding with the (suspected) winner in an election because anyone else is a wasted vote. Others are experts in these topics and I won't attempt to recreate their work here, I merely wanted to editorialize about the misidentification phenomenon. Back to the social contract.

|

Why should individuals respect the one institution which happens to be on top (usually through dubious means)? Well, nowadays, it's because you can vote which, at the national level, does about as much as pressing the floor button on an elevator multiple times to make it go faster. In countries where voting is optional, many (sometimes a majority) vote for "not voting." These people are the depressed realists. Some countries try to make a show of consent and punish the act of not voting. Compulsory voting, while it may give the illusion of consent, cannot be an actual sign of consent. (Though if they had a "no confidence" option which actually worked, it'd be better than now.)

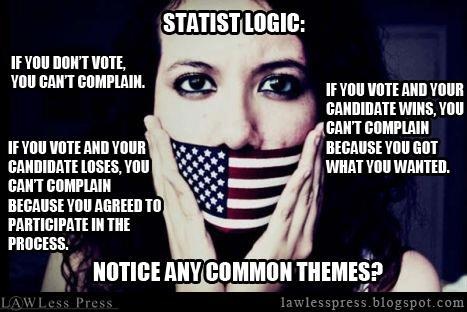

People who are trying to not be depressed or who are too ignorant to know what a racket voting at any non-local level is will tend to vote for the "lesser of two evils" (at least in first-past-the-post systems). By voting for evil, it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy that evil wins. Rather than address the systemic problems of voting (or, better yet, ditching voting altogether in favor of sortition), some group wins and the losers are said to have consented by: |

The first premise is false for those who don't vote or who are forced to vote under threat of punishment. The second is false for reasons outlined in an earlier section. The third is usually false in the real world because the parties in power set up impediments to others getting in and certain voting systems such as first-past-the-post strongly favor two parties. So, why should you have to obey the dictates of one institution of society which you don't really have a say in and is of questionable value? |

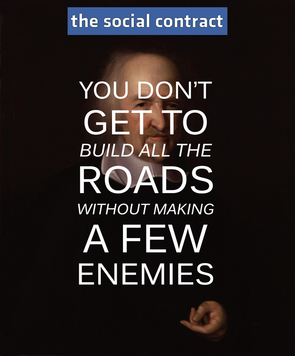

You're Getting the Benefits of Society (The Squeegeeman Argument)

Now, let's talk about the state. People operating in the name of or with funding from the state provide roads and education and a host of other public goods without the consent of everyone living in their jurisdiction. While some of the investments are actually club goods, truly public goods are non-excludable and suffer a free rider problem. I don't find it an unreasonable claim that "we all benefit from roads and a defensive military." My philosophical complaint remains: the receiving of an unsolicited benefit shouldn't oblige the receiver to compensate the producer in the case of the state any more than it does in the case of the squeegeeman.

The state takes taxes involuntarily to provide services which people in government then claim justifies further taxes since one is receiving the benefit. However, so long as one is paying a commensurate amount of taxes and the market is made inefficient by the state then that argument doesn't hold water - it has cause and effect reversed. A person pays taxes and then receives benefits. That's a conversion of goods. The transaction, at that point, is done and doesn't justify further taxation. Regardless, the taxation was not supported in the first place since it was taken before the state provided the services unless paid for on credit (which is making others an assumed party to a contract).

But, let's ignore the initial taxation and focus on the ongoing justification, particularly the part in italics. Let's say I pay $1,000 in taxes for defense (not offense) and get $2,000 worth of defense in return. The state could make the argument that I owe them $1,000 afterwards thus at least providing the pretext for perpetual taxation. However, that presumes that only the state can provide that much defense per unit monetary cost and only if a sufficient percentage of the population chips in.

|

The state tends to prevent people from forming private armies and militias. Maybe that didn't work out so well in the past, but maybe it would now. Technology is a great equalizer and, for a purely defensive force, maybe it's enough. Maybe, due to their being price feedback, it'd actually be cheaper than the government. Or not. But costs are measured in more than money. What if people value the freedom to decide more than they value the money (at least up to a certain degree)? Too bad, so sad for them?

Even if the state is the least expensive provider of public goods, so what? Does that oblige me to go with them? I can buy a book on calculus which helps me complete a degree and get a concomitant salary boost far in excess of the price of the book. It's certainly cheaper than trying to rediscover calculus on my own. Does that mean I owe Newton's (and Leibniz's) estates the difference? Barring some who claim that patents should be eternal (and I believe those people to be idiots), no. If I find out that something is worth it (and, remember, worth is subjectively determined), then I'll go for it. |

Even if free-riders on positive externalities are a problem, there are non-centralized/non-state voluntary solutions to that problem. The first is called dominant assurance contracts. The second is called shunning the hell out of freeloaders. Maybe those didn't work in the past before always-on worldwide communication networks. Do they now? We don't know because the state doesn't want others to try.

Lastly, am I obligated to buy the entire package if I get a benefit from part of it? Let's take a ridiculous example: there's a cupcake factory which makes the town smell nice. Unfortunately, it forces stores to buy their cupcakes and occasionally has to shoot someone who disagrees. I'm not a store and I don't buy their cupcakes, but they begin to demand that others in town are benefiting from the pleasant smell of vanilla wafting on the breezes. What if I'm fine with paying for the benefit of the smell, but don't want to support their strong-armed tactics?

Now apply any number of state-provided "goods." Do I like having the roads and NOAA and The Coast Guard? Sure. Should I be obligated to pay for the DEA, and offensive wars? Take the offensive wars part - I benefit from cheaper petroleum at the pump. Would I pay more for it? I don't know. But I suspect I'd rather find out than kill people I have no personal beef with. I'd argue that I'm coming out behind even if I ignore the killing in my name; taxes, dollar devaluation, a militarized state, pissing people off so as to make retaliatory attacks more likely later should be factored in if one cares about those things. I still buy the gas because having cheap fuel while killing is done in my name is better for me than having killing done in my name and no fuel.

So, if I am obligated to buy in if we all can save (I don't feel I am) and the government periodically checks to see if there are non-state solutions which work (they don't) and they do not interfere with the implementation of those (they won't) and somehow justify the initial taxation before services rendered (they can't using social contract theory), and I can pay for the good but not the bad (I can't) then the social contract justification of rights and the state is a great piece of moral political philosophy. Otherwise the state is just a well-armed man washing windshields unsolicited.

Practical Arguments

- Government is a necessary evil - debatable, at least in the "involuntary government" sense. I've outline one potential solution and I'm not even that smart. It's the 21st century for crying out loud, how about some new ideas on the provision of public goods and protection and law?

- Most people want safety over liberty - I suspect this is true, but I don't care about what those other people want until and unless it prevents me from getting what I want. I think a case can be made that liberty, over time, allows for effective defense in a wide range of environments even if in the short term it's turbulent. People could have safety in smaller states with more control while others could have liberty though there would remain a question about whether, if free states are more productive, less free but more militarized states would want to wage war against them. I predict it's a choice between more freedom and greater likelihood of foreign enemies or less freedom and a greater likelihood of domestic enemies within the apparatus of the government itself.

- Society was here first and it's not its fault there's nowhere left - it might not be their fault but it can become their problem when "the dispossessed" decide they want a share of access to nature or society. If scarcity makes it so that there are no alternatives to warfare, then no appeals to justice can be made when warfare breaks out. What the "love it or leave it" crowd neglects is a third option "overthrow it." That option may be denounced on grounds of practicality, but it can't be denounced on grounds of justice so long as there are no other reasonable options.

The Social Contract - A Lazy Idea

The Real "Social Contract"

- People identify with others in their "tribe."

- People agree to not do certain things to others or to do certain things for others

- People have expectations of others to do the same

- People come to similar conclusions regarding what constitutes excusable and inexcusable failures to perform and punishment

Boom, social norms. If you notice that government is missing from that list, congratulations, your eyes work. It's absent because it's not necessary. Now, someone reading this is going to say "but without government people would just kill one another!" Really? Is the law the only thing which is preventing you from killing another? No? Must be all those other people then! Seriously, most people are good in situations which allow them to be.

The real social contract is between individuals - just like the source of rights. That means that:

- It's mutable

- It's impermanent

- There can be more than one operating at the same time

- Government is not necessary (social contract, not government contract)

- It can have "weird" exceptions that make it not appear "universal" (remember, "similarly-situated" has value-laden dependencies)