Against Universal, Absolute Moral Systems

Though I have long been in the relativist camp, it took a long time for me to let go of the last vestiges which kept me in a moral realist mindset. Being useful and being true don't necessarily overlap. I put universal, absolute moral systems into that category.

Be sure to read Morality in One Lesson first to make sure you and I are on the same page regarding terms.

This is going to be a long post, so grab a beverage and open a text file to record all the assertions I'm making which you think are rubbish.

Assumptions

1. Reality exists, and can be expressed in terms of information or structures. To say claim that something exists is to claim that it is contained in the set of all information or structures. This, by itself, does not say how something exists, or the context in which it exists (other than the real which all expressible contexts are within). Real, unfortunately, has at least two connotations:

- Extant - it can be found in the real set. Unicorns are extant... as concepts. That is, there are one or more structures or slices of information which represent the concept of a unicorn.

- Concrete or instantiated - it can be found in the real set outside of the context of a mind; it is not mind-dependent (though, of course, it's definition and the delineation of its traits would be). By this standard, unicorns aren't real.

2. With any concept, the referent either exists as an instantiation or it doesn't, or there are states of structural or informational arrangement of reality in which the referent exists as an instantiation or there are none. The latter can only exist conceptually or as an incomplete/abstract simulation.

3. All verbs represent action, and action is only observable by state change. Without state change, no action has taken place.

4. "Nothing can't." Nothing can exist as a concept, but cannot be instantiated as there is not set of information or structural arrangement which can represent it. While the concept of nothing can affect things, nothing cannot. The corollary of this assertion is that anything which "verbs" is not nothing; it must be at least extant if not concrete.

5. A system cannot prove itself; proofs add information which must be proved, ad infinitum.

6. Truth is a property of beliefs. The sun isn't true, it just exists. The belief that it exists can be true or false. I hold to the correspondence theory of truth: beliefs are mental maps, and the truth of specific beliefs is how closely they match the structure or information of reality. I also hold that truth can exist between parts of the map, for instance a triangle has three sides is true by virtue of it being part of the definitions' truthmaker. That a pawn can move two spaces the first time it is moved is true relative to the rules of chess.

7. Justification and legitimacy only apply to items in the mental map relative to some standard. The sun cannot be justified, it just exists. Belief in the sun can be justified (or not), assertions that it should be worshiped can be justified (or not). That a pawn can move two spaces the first time it is moved is legitimate relative to the rules of chess.

8. The future will be like the past in the rules which govern the transition from state to state (if you believe time exists) or in the interconnectedness of a static "crystal" of reality (if you think time is an unnecessary variable).

9. The truth of an assertion or belief may be contextual, that is, it may have certain variable dependencies which affect its truth value. There is an "outermost" context, reality. There is nothing outside of reality and nothing reality is dependent on. If something was not noticed before, it is still part of reality, not outside of it. Per #4, only the extant can affect the extant - there are no "ghosts" or "different planes of existence" which operate on separate rules; any planes of existence are part of reality and are under an overall set of rules governing interactions.

10. The default, relatively safe stance on anything is that of its non-existence. There are far fewer things that do concretely exist than could be conceived or defined into existence. There are far fewer extant concepts than arrangements of information or structures which could define a concept.

Goal

I am doing this because I believe that my goal of increasing the number of successful human goal actualizers requires it. There's a reason why science takes the ball from philosophy and scores the touchdowns: it's not so focused on defining terms and "term purity" that it can get things done. (I know that science is itself a philosophy, so don't bother commenting on that.)

What I'm not going to do is reference the S.E.P., namedrop philosophers (except one thing by Hume) or ethical systems or positions. I'm not hubristic enough to assume that I figured out something that some of my predecessors haven't, but sometimes it's helpful to not have too many preexisting ideas distracting one from the search for what corresponds with experience.

Claim 1: All uses of the word ought either reduce to expectation or advisability

I'll wait. Just because I haven't figured it out doesn't mean it's not a soluble problem.

Or perhaps you've come back with "oughts don't work like that!" Well, then we're going to have a problem, because of my assertion that "nothing can't." If you're claiming that an ought exists, you must have some evidence for it, it must have left a mark on reality - which it can only do by changing the states of reality, or taking action, or "verbing." Nothing (not the concept, the actual thing which doesn't exist) cannot logically leave a mark, therefore oughts must either exist as a concept or must be locatable in reality as something concrete, which can affect reality.

People misinterpret Hume constantly. Hume's famous is/ought gap touches deduction, induction and justification. It does not say that you can't make ought conclusions statements solely from fact premises, just that you can't do so in a way which does not logically follow.

The expectational form of ought can be of the "if you're actually doing X by the definition of X, then there are certain norms that are required" type. That may or may not have to do with morality, but most common uses which are that strict don't tie to morality. They are rarely controversial. "If you're doing arithmetic correctly, you should get 4 for 2+2." (italics as hidden premise) is a deductive ought because 2+2=4 is deductive given the definitions of those symbols and their relationship to one another. An inductive expectation is "The sun ought to rise tomorrow given the corpus of our experience about physical laws being constant." While we can't know that it will as we don't yet have information entanglement with its rising on predicted day, we'd be bad Bayesians if we didn't expect the sun to come up tomorrow.

What these two examples of expectation have in common is that they're what is expected from the universe unfolding sans agents. The sun will come up tomorrow even if there are no agents left in the universe. 2+2=4 is defined in such a way as to be true (factually correspondent) even if there is no thought anywhere. Even though agents are without contra-causal free will, there are other forms of the word which deal with the universe unfolding in an agent-dependent and unpredictable way. The first of these is advisability.

The most common day-to-day form is straight up advisability, the instrumental ought. You "ought to go to the doctor when sick and you want to not be sick and the doctor can make you not sick." That's hardly a controversial statement even though it reaches an ought conclusion from is premises. Now, someone is going to come along and say that one of the premises is a not-so-hidden ought statement (by turning "want to not be sick" into "ought to not be sick") or they'll argue that ought doesn't mean the same thing as "want to make/keep a state of affairs true." To the latter I can only say "give me a better definition that can actually exist in a non-dualist reality, and which captures the way people behave." To the former, I say "nope, that's just a vanilla (non-ought) is statement. The agent may experience it as an impetus and defend it with 'ought-type-language,' but it's just non-ought statement with a truth value.

|

With "straight up" advisability, oughts can only tie means and ends; it can't tie multiple ends together without going through means which tie them together. Ends are just things which exist as goals or dispositions and they don't need to be justified any more than "butter tastes good" needs to be justified.

This is where people start getting into trouble in the way that Hume was decrying. Facts are "turtles all the way down" - facts can only be justified with other facts which themselves need to be justified. That's the whole point of axioms. Values are a specific type of fact which can be logically justified like any other fact but can only be "advisability justified" (e.g. used as an ought) by reference to other value facts. This is why the open question exists. I can logically be justify in making a claim about the existence of a value (e.g. Jeff finds pain to be "bad"), but I can't, in a non-value-referencing manner, justify that "pain is bad." There is no terminal value to reference. |

It can also deflate into advisability, usually from the context of the one making the claim (not surprising given my story about what morality is). This can be shown by using the 2 year old/Socratic method; just keep saying "why?" until you hit a circular reference or an end point (the third option, infinite regress is not a possibility here, I promise). The eventual answer is always "because I want X" or, far less likely in the case of moral statements "because Ibelieve you want X."

Universality is not possible in the way humans are trying to use it

Universality is problematic once it is realized that:

- Almost anything can be a universal rule. Sure, the rules may be costly to operate under (which may lead to a lot of "special pleading" (everyone is a practicalist when push comes to shove)), or the rules may not last, but they can be universal. Take the common human use of moral universality: "the same rules for similarly-situated individuals." If this wasn't the case, then treating all humans the same would demand reparations from a 2 year old who knocks over a display case. Children are considered "differently situated." Non-human animals are considered differently situated as well. The common justifications are because "they don't have souls," or "cannot reason" or "would just crap all over everything." All of these (except the first which isn't provable) can apply to human children or, worse, the severely mentally handicapped. That means that these reasons are bullshit as evinced by the hypocrisy among claimants who won't take their claims to their logical conclusions, but they sound good to both the claimant and others. And that's all that ultimately matters.

- Hume said that "reason is the slave of the passions" and I see that strongly in the concept and practice of rationalization; the desire circuitry wants something and the logic circuitry finds any number of reasons to sell the desire as justified. Applying the same logic to other distinctions reveals this when most people don't value the distinction and try to come up with ways to de-justify it which are equally arbitrary. The thing is, all agents are differently situated because they're not the same agent!

- "Black people are differently-situated than whites," "women than men," "agents I experience the qualia of (me), versus agents I don't experience the qualia of (everyone else)" "the strong than the weak." Each of these were (and sometimes still are) points of division. One can then make universal rules which apply to thou but not to thee. The last one is especially powerful because it appears the least arbitrary: clearly the universe is allowing the strong to be strong and they therefore have less need of a coalition than the weak, why should they not impose their will on others? No one gets to make a claim about what's pertinent in morality and actually pretend that it's more than a value they're trying to stick into the system. Skin color can be as pertinent to morality as self-awareness. The universe sans-agents doesn't "care."

The naturalistic fallacy: fun for the whole evolutionary family

|

The universe doesn't care about you. It doesn't like you, it doesn't hate you. Parts of the universe known as agents may like or hate you, true, but just parts. There has been no indication of values written into the fabric of the universe itself, unless all disposition is value (i.e. oxygen atoms "value" bonding with other oxygen atoms) - which is fine, but it makes a lot of language useless. Natural selection is a blind process. It's not leading up to anything better or worse judged from nowhere. There's no devolution, either. If humans slowly turn back into fish, that's not a "de-progression" or "devolution" or anything like that, it's just change.

|

Depicted: not "devolution" - and, in this example, not evolution either.

|

I consider it unfortunate that people try to unconsciously attribute goals to something like evolution and then use that as an argument for moral realism while denying that evolution is actually an agent or has goals. Social or individual survival gets defined as the goal which all moral rules answer or, worse, the purpose of moral rules. Those who are truly believe that evolution has no goals will be forced to say something like "genetic predispositions to behaviors which are not overly-detrimental to individual and social survival are not selected out of the general population" and "social creatures may retain and spread normative memes and predispositions which are not overly-detrimental to their survival." The prefix "overly-" is open to debate but I'll define it as something like "will lead to social extinction in a few generations if practiced by >10% of individuals" or, for individual extinction, "will cause one's genes (going forward) to be selected out of existence in a few generations."

What works implies goals because a definition of works will be value-laden. The only quasi-substitutable value-free phrase is what's possible but that doesn't provide the possibility-constraints or long view humans want from norms. There's already a generally accepted moral precept which handles that case: ought implies can. Things are possible until they aren't and a lot of behaviors which would be selected out of existence in the long-term can slide by in the short term. If possibility is the yardstick, then anything which is possible is good until it is selected against. Since it is impossible for evolution to be forward-looking or otherwise intelligently probabilistic, humans must be predicting and evaluating to derive a subset of possibility which is normatively-acceptable.

This is where libertarians and moral realists in particular get hung up: "but if you went in the experience machine (or, for Kantian libertarians, if everyone thought murder was ok), you'd die in a week and society would collapse." So what? Natural selection's judgments are not human judgments. Natural selection "says" slavery and parasitism are "good." Natural selection "says" that spending time in leisure activities that don't increase the ability to convert other organic material into your replicator building blocks is "bad."

If people are making the claim that what's evolutionarily successful behavior is what's moral, then they have to take the argument all the way: genocide is fine if your tribe wins, rape is fine if she gets pregnant with your child. I recently found this article (and heard on RadioLab) that, if you starve a boy 9 to 12 years of age, it gives his descendants a huge health boost. If "what evolution wants" is good then starving a young boy for three years is good so long as he has children later. But suffering! Well, there's less overall suffering if the boy takes one for the team presuming that the odds and the badnesses can be compared (which they can't). How the hell do you square that circle? Humans can do better than adopting the "moral axioms" of a blind process.

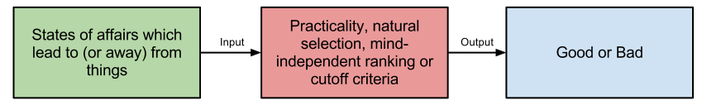

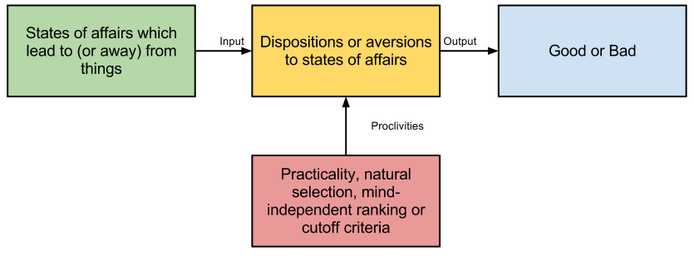

Breaking Down Objective: One-Step Versus Two-Step

What's considered normatively good or bad is mind-dependent as dispositions and aversions and desires exist in the mind. But wait! People can be wrong about their beliefs. Sure, but then you need something outside of agents to appeal to - beliefs can be compared to reality. Desires can be compared to ... what? Means must answer some end - what is the end? How is that not arbitrary? The universe is doing a lot of things which appear conflicting - making and killing life, making and destroying stars, etc. How does one tease out which disposition to hang moral rightness off of? You either throw your hands up and say "everything possible is allowed" or you introduce a discriminator which is a subset of possibility.

It appears to me that moral realists want to say "some things work for human survival or flourishing or the well-being of conscious creatures" therefore moral good. They try to get to moral rightness in a single step without having to go through the mind of an agent. However, there's still a value judgement in there and values are solely the domain of agents. The only way out of that is to consider the process of evolution mildly intelligent and imbue it with values. Even then there's a lot of things evolution allows which humans don't like. Creating a further distinction between the good things evolution does from the bad things it does requires another value judgement!

- Truth? Nope.

- Not killing others? Nope.

- No taking things others made? Nope.

- Treating others the same as yourself or those you care about? Nope.

All of these things can and do happen with various justifications and the process of morality (not merely any specific moral system) work. If morality was that fragile of a process, social creatures would have never survived for as long as they have.

While I haven't scoured the entire internet, I've only heard this tact taken by anarcho-capitalists which is funny considering that no large-scale anarchistic society has "worked" according to their own standard. It's either always collapses or is conquered from without or from within. Even if it's captured from without, that indicates that its maladapted to an environment in which nation states and statist armies exist and thus not having a government is bad. Inasmuch as government and protection need to be paid for involuntarily through taxes, then taxes are good. I've heard exactly ZERO people get behind that idea when their only out would be to argue that funding a military could be voluntary or that modern communications and social structures now make large-scale an-cap societies possible.

Step 1: Facts of genetics or environment cause agents to have dispositions toward or aversions from things.

Step 2: Dispositions toward and aversions from things lead to wanting to change others who are doing the opposite or endangering what you want.

Therefore: morality.

What agents consider morally right or wrong are objectively caused - sure. There's nothing that's mind-independent about it though. Everything is objectively caused but only where it intersects with shaping the desires of agents does it have the possibility of becoming an ought.

Humans don't need to wait for such technology to find moral disagreement and all the problems it entails for moral realism because...

Humans want conflicting things.

|

Shocker! Haidt and his merry band of anthropologists have identified no less than six moral foundations. There are probably more. These foundations almost certainly have genetic components, but the expression of genetic components often requires environmental activation. Thus the nature and nurture argument is largely a waste of time. Talk of "human nature" seems to linger on because showing that most humans (the group our coalitions are most likely to care about or fear (often the same thing)) share generally compatible values makes developing moral systems incredibly easy. Ignoring a few outliers, all that needs to be corrected are people's beliefs and POOF, perfect world!

|

Go ahead, optimise these six foundational values...

|

Some of the foundational values can contradict in common scenarios, making the possibility of satisficing unlikely. Authority and freedom, freedom and care, care and purity, etc. etc. Come closer, I want to tell you something... there is no a-contextual "right" answer in judging these things because judging IS the part of the context. Conservatives adopt all 6 values to varying degrees. Liberals only 3. Libertarians probably around 3 but are overwhelmingly biased towards liberty. I am strong on 3, moderate on 1 and weak on 2. If is highly unlikely that there will be agreement, even narrowing the universality of a ruleset to competent adult humans once you get away from "cereberal cortex wiring" such as "pain sucks." The likelihood of agreement shrinks with the number of humans, and the number of "hard dispositions" to balance.

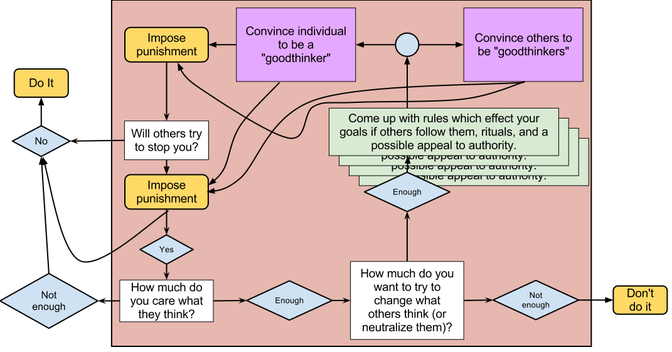

How Morality Plays Out in the Real World

Courtesy of Jayson Walls

Still, for the purposes of the study of the operation of morality, this consideration isn't particularly necessary; it suffices to say that agents have things they like and dislike and they form coalitions. When one is trying to formulate moral rules, study of the source of likes and dislikes becomes pertinent inasmuch as then the strength of likes (genetic predispositions are stronger than cultural ones) and the distribution of likes (genetic predispositions for foundational values are typically more common than cultural ones) help formulate inexpensive rules.

The green boxes represents a moral systems.

These moral systems comprise the moral ecosystem and compete with one another for mindshare (purple boxes).

Ones which are expensive to practice or lead to results which kill their hosts will be selected out of existence.

They are always knowingly or unconsciously created by agents and answer the goals of agents whether those goals are deliberate or instinctual.

Consistency and Moral Persuasion

As far as I’m aware, there’s no sound theoretical support for the idea that moral facts exist. The things that we call moral decisions, like any other kind of decisions, are decisions made in accordance with the actor’s subjective preferences (for instance, an actor may prefer to minimise suffering). I wouldn’t use the word 'justified’ in this context though, I think 'explained’ is a better fit.

The conern about justification may have to do with a worry that without a conviction that moral facts exist, and that are discoverable, moral persuasion becomes impossible.

But that’s not the case. Moral persuasion always relies on appealing to shared convictions about the answers to moral questions. It doesn’t matter whether these convictions are a 'mere’ preference, or reflections of a truth written into the fabric of the universe—either your interlocutor shares them or he doesn’t. To the extent that he does, moral persuasion is possible.

For instance, in the case of the spanking parent, an attempt at persuasion may be 'bootstrapped’ by appealing—probably implicitly—to the agreement between you that the goal of minimising suffering is desirable. You might then go about trying to show that spanking is likely to work against this goal.

-bitbutter, http://www.asktheatheists.com/

|

In my opinion, the author of that quote nails it. I want to take what he says about moral persuasion and turn the discussion to something which angers every moralist I've met whether they're moral realists or not: the consistency of moral rules only matters to the extent that it allows the moral system to function. More specifically it only matters to the extent which it allows moral persuasion and adoption.

People seem to deify consistency as if it's good for its own sake. To be fair, a consistency check will quickly signal bad maps; so far as we're aware reality is self-consistent so any map which isn't consistent with itself within the same contextual perspective has at least one error. Goals don't have a truth value and varying means can all be effective of goals so long as efficiency criteria are variegated. Individuals can change goals, sometimes as a group. Wouldn't that be a different moral system? Yes and maybe. The token would be different, but the type could be the same even with differences in moral rules so long as the goal was the same (and, presumably, the moral rules were effective of that goal regardless of how efficient they were for other goals). All humans are different but, definitionally, they are all humans. Many sects of religion can be lumped under Christianity but have different efficiency criteria which apply to the main goal of spreading the word of Christ (yes, I know that some lumped under that heading don't even share that goal). It took me a long time to stop deifying consistency or truth - even though I still do my best to weed out inconsistencies rather than hitting the mute button on my cognitive dissonance alarm. |

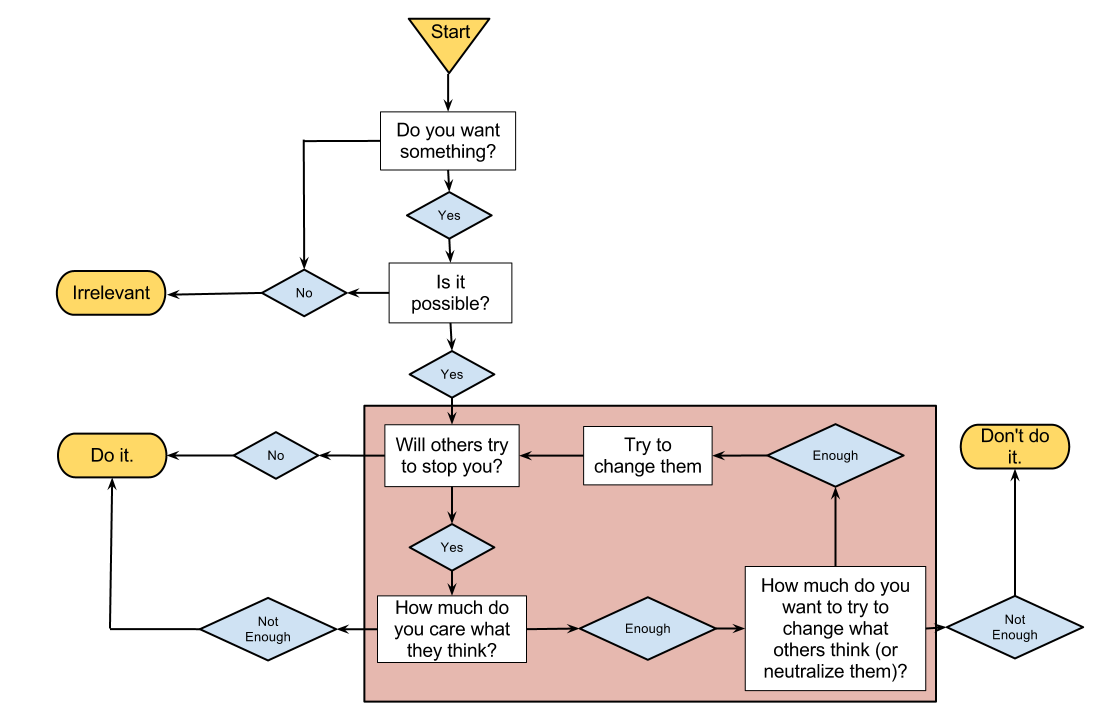

There is no "ought from nowhere"

So, take a hypothetical question whose cousins are bandied about on the internet quite readily... If you could kill someone you wanted to see dead and no one would catch you and you wouldn't suffer guilt/higher gas prices/insert perceived bad thing here, then why shouldn't you kill that someone? Ready for the answer? It's a bullshit question! If someone can and wants to kill another then, from their context, it's advisable and they should kill that someone. If the context is shifted to that of the victim or agents who don't like murder, then they can say "you shouldn't because..." and then either go to punishments (which is saying "because you like being shot less than murdering") or point to moral rules (which is ultimately saying "murder? yuck!" or "murder? consequences no bueno/scary").

But doesn't that means moral oughts are relative to moral rules and moral systems? Yup. Get over it. But that means all systems are equal! False. That means that, outside of a context from which to judge, all values are non-commensurable. How many flapjacks is a doghouse? Both are logically incoherent questions and wouldn't pass compilation in any strict programming language.

The Moral Ecosystem

So now that we have a family of moralities, can we crown one king, and declare that to be the One True Morality by which all else is judged? Unfortunately, I think not. As far as an end-relational meta-ethics goes, as long as something can be used to evaluate, it is a legitimate standard that can ground normative statements. Likewise, these statements can be in genuine conflict, and still be individually correct without meta-ethical contradiction.Why might I insist this to be the case? Mainly because of a genuine puzzle about how a king or queen of morality may be crowned. In order to choose the One True Morality, you would need a standard of evaluation to figure out what makes for one morality contender better than that. And the only way to do that is by basis of an already existing One True Morality to play supermorality and judge the competition. But to do so would be to beg the question.

Final ThoughtsWhile humans want their moral systems to be value-free and universal, it's impossible to make such a moral system. However, the process by which morality works is itself value-free and universal - every morality-capable agent must and already does adopt it as a matter of course:

|

If desirism just adds this one recognition, it would be the most absolute and complete understanding of morality ever put forth by a philosopher. It's understandable that ethicists would want to shy away from it because the closer you get to that, the closer you get to might makes right which many have reasons to want to change - however they're still operating within that paradigm since changing things requires power (might).

This applies to moral eliminiativists too - you can eliminate moral systems, but not morality.