Shut Up About Free Will Already!

Free will is nothing more than a semantics problem. It's time to taboo words and make predictive claims. If you can't do that then you haven't actually explored the concepts that you're pushing around your head like so many chairs.

I aim to explain how free will is nothing more than a problem of identity and system opacity versus transparency. Move the boundaries and the problem (and apparent conflict) dissolves. I also want to lay to rest the bogus claim that free will is necessary for responsibility. If anything, I think a faulty conception of free will is responsible for the most wasteful criminal "justice" approaches practiced today.

Why am I bothering to do this since you don't have "free will?" Well, I don't have "free will" to not do it! That's the quick, conversation-ending counterargument, the conversation-starting argument is because you can still make choices and you can still change your mind or have it changed.

What Determinism Isn't

Determinism isn't about people determining what you're going to do, it's about future events being entirely caused by prior events plus natural laws. Let me draw the distinction with a movie metaphor.

|

This scene comes near the end of the movie The Shawshank Redemption. If you haven't seen this movie, apparently you don't have a TV since it's guaranteed to be on at least one channel once per day.

Andy Dufresne has just escaped from prison where he was held despite being innocent and is enjoying the rain as a free man for the first time in 20 years. He's also dousing off the sewage he had to wade through as he made his escape through a sewer pipe. I don't have the movie in front of me, but let's say this scene takes place around minute marker 160 (it's a long movie). |

|

Here's a scene near the end, but before the escape sequence. Let's say minute maker 145. What's going to happen NOW at marker 160?

The same thing! The same thing will happen at marker 160 when viewed from marker 30 or marker 145. That you're further along in the movie doesn't change the ending. Moreover, even if you can't predict the ending of the movie, it still has an ending. That, in essence is determinism. The movie is set up to play out a certain way and even if things appear as choices (to the characters in the movie, for instance), something will happen and it doesn't matter where you are in the story - the ending will be the same. |

Whoa! Whoa! Inevitable? Yes. Unfortunately for many people's psyches, fatalism must fall out of determinism; the future is immutable. If humans can't change past events or the laws of nature, then they can't change the future. Why past events, why not present events? Because, in determinism, present events are determined by past events. You'd have to somehow change the first event or the laws of nature to change all the events which follow.

Furthermore change the future is a nonsense term. Something is only the future if it will come to pass. If you somehow cause something to not come to pass then it's coming to pass was not the future and you didn't change from one future to another - you changed from a mental simulation of the future. I discuss this further below.

A Quantum of Solace

Ignoring that - even if randomness exists, there still has to be a strong causal agent to tie stimulus non-arbitrarily with response. If that wasn't the case, then people would try to walk through walls instead of nearby doors. They'd act completely disconnected from reality. Most people don't envy such people for their initiation of uncaused action. Most people feel bad and then lock those people up in sanitariums.

Determinism says you can't have free will. Non-caused outputs say you can't have free will.

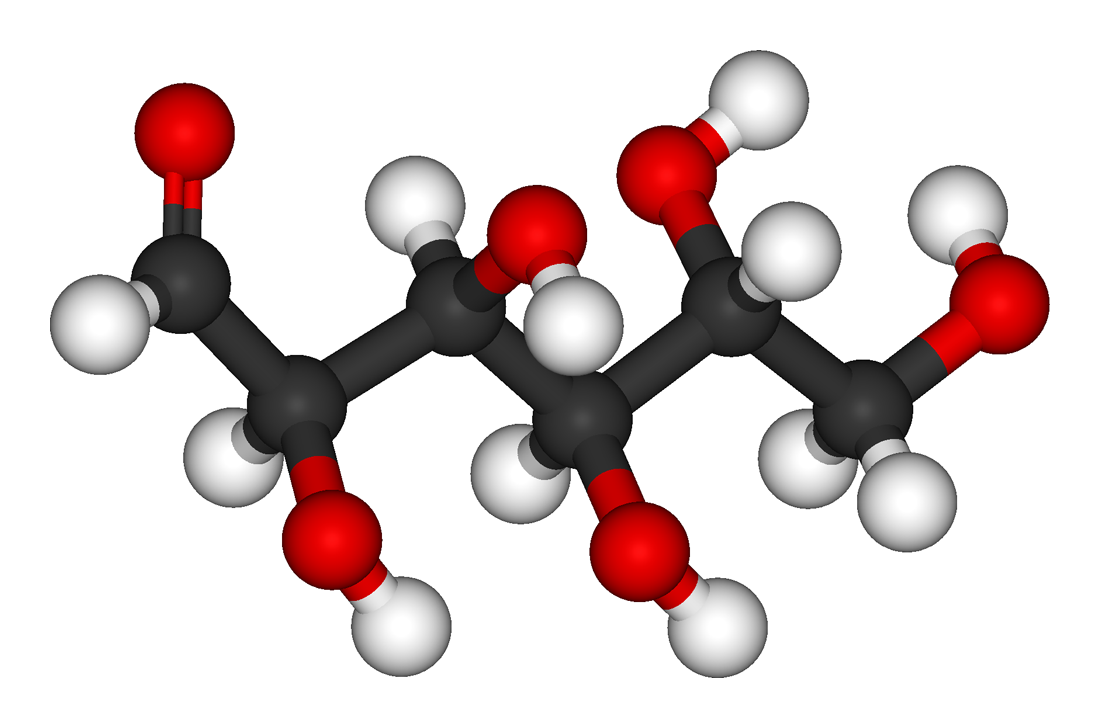

Remove Identity and then Build Up

Let's start by removing "higher-level" distinctions. All used distinctions between things are projected and exist in the map. While differences exist in the territory as well, agents can use different maps to highlight certain aspects of and relationships in their perceptions of the underlying territory and that doesn't mean one is more right than the other, though one may be more useful in certain ways than another. High level distinctions would include humans, trees, doors, all those things. Let's bring things down to the level of atoms and molecules. Atoms and molecules are, of course, still conceptions which exist in maps but they are "lower-level:" that is the provide fewer obviously useful distinctions - they are more homogeneous.

|

I'm going to use billiard balls for representations of molecules and atoms, since it's more fun to visualize and as a nod to Newtonian physics.

Let's start out with simple cause and effect, stuff banging around. Yes, I know that molecules and motion are abstractions too, but I need to abstract something out of reality to even be able to talk. Anyways, these molecules bounce around some consequences happen. The way that things will result depends entirely on the input, the rules of interaction, and quantum randomness. The output can be completely described in terms of those three factors even if it can't be predicted. |

|

This outline defines the boundaries of you versus non-you. Identifying such a boundary is only in the realm of the map-maker! Now, draw a distinction between atomic interactions which occur outside the box and those which happen inside the box and ... decisions appear! Inputs go into the box, outputs come out, decisions were made in the box even though the interactions in the box aren't qualitatively different than those outside of the box.

Now we bring things back up and we now have something which looks like a human - a box into which inputs go and outputs pop out. |

"Why are you trying to change me if it doesn't matter?" Well, firstly because I have to based on my current state. But, more importantly, because it matters that I do. If I hop in my car, I might not get to work - the car could crash or there could be a construction delay. But I have a surefire way to not get to work by car - don't get in the car in the first place. Nihilism is a waste of time. Things matter - to you - and they'll continue to matter whether or not you have contra-causal free will.

What Free Will Looks Like - Procedural Decision-Making

WingedWombat of Reddit nails it:

My view on free will tends to be simply that what we call free will is simply decision-making. An entity has a will to the extent that it can weigh and recognize different factors in its environment against past events and potential future contingencies and select among the various alternatives a preferred action. In this view, when someone says that people have "free will", all I really think that they are saying is that the human decision-making procedure is so complex that it is unfeasible, even for the person making the decision, to determine in advance of actually making the decision what the outcome will be (particularly given that many of the factors are consciously unavailable to the chooser). The decision is free insofar as it is not externally constrained, i.e. once the decider decides on his course of action, he is not prevented from implementing it in some way (obviously, I can't freely choose to fly, or to open a locked door to which I have no key, but I can choose to jump or knock on that door).

It is obviously ridiculous to propose that a decision can somehow be "free" of the past events leading up to that decision. Whenever someone says something like "If you can't choose differently, then you aren't really choosing", I get annoyed, because of course you are. The fact that your choice is simply the outcome of a decision-making procedure that takes the various situational inputs, weighs them, and produces an output in no way invalidates the fact that a decision is taking place.

You can have free will if those things can have free will or you can argue free will is the feeling of uncaused choice and keep free will (mostly) to the realm of humanity but degrade it to the status of a feeling.

Why Free Will?

Compatibilism seems to me to be a semantic compromise between a need to believe but an inability to do so: free will is defined as what we experience so that it can exist and that we can feel good about believing we have it. Well, I can claim that millionaire means having whatever money I happen to have in my pocket at the time and maybe I'll feel good about myself, but I'm going to run into some trouble at the Maserati dealership. If the purpose of language is to transmit ideas, perceptions, and expectations to one another then words have to constrain those things. Words which allow anything are not communication. I could redefine pizza to mean "food which tastes good" and then make the claim that "everyone likes pizza." That ends up being a mere disguised tautology and it conveys no information. Similarly compatibilism is defined in a way which ends up as "free will is what people have." Ok. How is that useful? How does that constrain possibility space? What predictions does it allow?

Why does this Matter?

People who are true believers in free will tend to judge people for their bad choices rather than seeing that, if they were in that person's shoes there's a strong possibility that they would have made choices which were substantially the same. They justify punishment of the bad instead of adopting a "there but for the grace of god go I" attitude and focusing on causes.

The U.S. locks up more people per capita than any other country. These are people who have been labelled "bad." Instead of finding the reasons why people act in certain ways which often lead to socialist-/excuse-sounding problems like "bad parents," "being poor," "lack of opportunities," they are thrown into "correctional facilities" which don't actually reform the people in them. Those on the outside get to feel like justice is being served and they get an ego boost knowing that "they're a good person" unlike those dirty crack addicts and prostitutes in jail. It comes at the expense of human actualization - which is what my moral system promotes.

It's possible that those humans could be productive members of society if conditions were changed. Even if they can't, there are new crops of humans destined for what amounts to a wasted life. Change is hard. Identifying with those who disgust us is hard - we have a disposition to not only want to separate ourselves physically from such things, but also separate ourselves emotionally. Since I don't grant people a right to be wrong, I demand that they own that which they value more - human actualization or feeling smug and being lazy and thinking that the world operates on black and white principles.

The other "selfless" reason I have to promote the truth about free will is that I don't want people to ignore power disparities and technological and psychological mind hacks. If people believe that they have free will - that they are the author of their own actions regardless of input, that moves beyond a lack of humility to outright hubris. What are the chances that scientists cannot design an unhackable computer with millions of hours of peer-review, but that a blind process such as evolution could cobble a working brain together in a way so as to be shielded from attack? Yeah, that's what I thought - sounds retarded when you say it out loud, doesn't it?

People who believe they are unhackable won't take the time to see how influenced humans are by large media players, by those in power - to keep them either chasing or running away from shadows. False flags, hell - flags in general - pledging allegiance to a symbol? I'll be the first to say that ritual and habit are important for cohesion and being a good moral practitioner if you're choosing to give such things power mindfully. Otherwise you're either coasting into them or reacting into them and those who understand power relationships probably find you useful.

Responsibility doesn't Require Free WillNo. The Hell. It Doesn't. My final reason for preaching the truth about free will is especially personal and I touched on it in the opening. I'm honestly sick of hearing the debate. Even if I can overcome people's gut reaction to flip over the board game and storm off after being denied the type of free will they want, I'm almost always presented with the old "but then you can't hold people responsible" standby. In what other arena can demands be made that human convenience is what determines reality? Sorry, reality dictates that contra-causal freedom doesn't exist unless it's random in which case it's not willful. Period.

|

Correction or neutralization requires scarce energy, so it makes sense to figure out who to direct corrective or neutralizing efforts towards, the form of those efforts, and the proportion of those efforts to direct to any given individual. It makes sense even if you can trace the things which happen now back to the trilobites and call them causally responsible. As long as a time travel costs infinity units of effort, it's pointless to try to change the behavior of trilobites.

There's a difference between being a causal factor, faulty, and blameworthy/morally responsible. One is causally involved if one is anywhere in a causal chain leading up to an event. If you're in the same light cone as another, then chances are you're a causal factor for something bad which happened somewhere. Eliminating all effects or being omniscient about one's actions isn't going to happen any time soon because it's wholly impractical: it costs too much. Any moral system which respects ought implies can cannot conflate causal responsibility with moral responsibility.

Faulty simply means that something isn't doing what it's "supposed to." Animals and machines can be faulty if they act in ways others wish they wouldn't.

Morally responsible/blameworthy means that not only is something faulty, but that it's worthwhile (worthy) to blame it - that blame (or punishments and threats of punishment) can change its behavior such that it better effects a state of affairs you want to see exist. This rules out computers and the insane - those agents may have to simply be neutralized instead. Praiseworthy is the other side of blameworthy - it's worthwhile to praise an agent to get it to continue or increase doing what you want. Being responsive to social tools such as discussion that isn't really praising or blaming still fits in the category of responsible even if it doesn't make someone praiseworthy or blameworthy.

For moral responsibility, I like breaking the word responsible down into response-able, able to respond. Morally responsible agents are able to respond to socially-applied non-opportunity-neutralizing corrective efforts. Proximity to the event doesn't matter, the cost/benefit calculation of correction does.

The ability to respond is orthogonal to being faulty. However it's used as a normative term on agents who are singled out only when they are believed to be faulty. Blameworthiness is the intersection of responsible and faulty. Things which aren't responsible aren't blameworthy even if they are faulty. Such things may be correctable, but aren't correctable through the tools of praise, blame, punishment and reward. Things which are morally responsible are always correctable through social tools. For instance, a man who developed pedophilia due to a brain tumor would need to be corrected by surgery or neutralized by being locked up. No amount of yelling at him or talking it out was going to fix the problem. He was faulty but not responsible.

|

Or... take Son of Sam. His neighbor's dog was a causal factor in his killing multiple women. Sure, if it wasn't the dog it'd probably be something else, but that's the way reality unfolded. One could focus on eliminating dogs, but that's expensive: dogs are useful, dogs are loved, it'd be hard to track down every dog. Furthermore, most people don't flip out when they hear dogs barking. Son of Sam was faulty because his programming couldn't handle input which didn't cause buffer overruns in most of the population. If punishment and shaming wouldn't work on him, then he wasn't blameworthy - he was unable to respond to having his desires changed - he was not morally response-able. That didn't mean he didn't have to be dealt with. Neutralizing him by locking him away was the cheapest solution.

This view of moral responsibility doesn't require free will. A computer has as much free will as a human, but I can still reprogram or dispose of it when it starts failing. I can do the same thing with humans and for the same practical reasons. This whole outlook requires that free will not exist otherwise non-neutralizing corrective efforts wouldn't be successful, which we know they are - at least sometimes. |

| Definition | Compromise |

| Being able to make decisions | Computers and non-human animals have free will |

| Using deliberation and rationality to make decisions | Some non-human animals might have free will, most decisions you make will not be from free will as they are Limbic-system-conclusive |

There. I've laid out how it works and why it works and why the discussion was important. Now, can we please, please shut up about this topic forever?