Ought Implies Can

An apartment is on fire and, on the top floor, a child is trapped. This child will die unless rescued. The fire department is unable to get to the top floor. You are on the street witnessing the fire. You fail to teleport the child out because, like all humans, you are not capable of teleporting matter*. Ought the bystander to have teleported the child out?

There is a widely accepted ethical precept that ought implies can - that a moral system cannot "reasonably" make moral prescriptions which are impossible to follow. This is an almost universally prevalent human intuition. That doesn't guarantee it's correct, but it does make it worth investigating further in my opinion.

Challenges to ought implies can exist. But I want to first mention something which I don't consider within ought implies can: the concept of can implies blameworthiness.

I will cover that potential confusion early.

I will warn you ahead of time that I'm using definitions which I consider coherent for ought and can. With most of these definitions, ought implies can. For other definitions it may not, but I'd want to be shown that those definitions even map to something real before debating about the implications of using those definitions for ought implies can.

There is a widely accepted ethical precept that ought implies can - that a moral system cannot "reasonably" make moral prescriptions which are impossible to follow. This is an almost universally prevalent human intuition. That doesn't guarantee it's correct, but it does make it worth investigating further in my opinion.

Challenges to ought implies can exist. But I want to first mention something which I don't consider within ought implies can: the concept of can implies blameworthiness.

I will cover that potential confusion early.

I will warn you ahead of time that I'm using definitions which I consider coherent for ought and can. With most of these definitions, ought implies can. For other definitions it may not, but I'd want to be shown that those definitions even map to something real before debating about the implications of using those definitions for ought implies can.

The Easy Part: Blameworthiness

I take blameworthiness to quite literally mean "worthwhile to blame." Someone is blameworthy if blaming that individual is useful in some way. There are numerous reasons why someone might want to blame another, and some of them may entail ability to do something while others might not. My standard for blameworthiness is faulty + responsible (successi

{ Take the kid who didn't finish shit. You're using his laziness as a proxy to determine that he's faulty. Punish his ass even if he can't... }

{ Take the kid who didn't finish shit. You're using his laziness as a proxy to determine that he's faulty. Punish his ass even if he can't... }

What about Contra-Causal Free Will?

Wait! Don't I have a page saying that contra-causal will doesn't exist? If our bystander acts randomly or was determined to not attempt to rescue the child, then why hold him in contempt for failing to do what was impossible to do?

We don't blame a rock for rolling down a hill. It couldn't do otherwise. Isn't it unfair to blame people who couldn't do otherwise?

My position is that blame and praise are instrumentally valuable; yelling at a rock won't reduce future incidences of it taking or failing to take an action. Yelling at humans very well might. We can't be sure that blaming or praising a human will bring their desires in line with those of the one applying the social pressure. However, there's overwhelming statistical evidence that people who are expected to behave in a certain way (and where those expectations are backed by punishment or reward and blame or praise) are far more likely to behave in that way than those who don't. That makes blame and praise a rational thing to apply as the default position (if it were known that an individual were a sociopath or mentally damaged such that blame or praise had no effect, then it would be irrational to apply such methods).

Ok. So blaming people makes sense while blaming rocks doesn't even in the case that both lack contra-causal free will. That still doesn't restore "ought implies can." Applying blame to someone to fix future behaviors is still saying they ought to have done something different than what they did do. They couldn't have done otherwise without contra-causal free will. Therefore ought does not imply can.

Perhaps this is why free will advocates get so up in arms about blame and praise being incoherent in a deterministic world. Even if there are practical considerations for applying praise and blame, that one ought do something which they cannot flies in the face of intuition. How long should my prison sentence be for failing to stop the holocaust? Never mind that I wasn't even born when it happened. If ought doesn't imply can, most moral intuitions are out the window.

I propose that "ought implies can" is only false in a deterministic world where the word "can" is used as "ability." One doesn't have the ability to teleport matter. One doesn't have the ability to fly (without technology). One doesn't have the ability to decide to instantly be a great chess player (or "choose to win"). One doesn't have the ability to choose outside of the constraints reality places on them. In determinism, those constraints are absolute.

If "can" is used as "possible," then things change so long as one is honest about possibility. Possibility and probability exist in the mind - they are not part of the extra-agent territory of reality. If you have cancer you'll either get better or not. There's no "80% chance of remission" outside of your mind. That statement is an expression of the epistemological ignorance one has about all of the factors which will lead to one case or the other. If you were fully informed you'd either know what would happen or, if actual, REAL randomness exists (aka even reality doesn't "know" what it's going to do), knowledge would pretty much be impossible.

I'm not saying you can't point to mind-independent things and declare percentages, averages, etc. so long it references a past or current state of affairs (namely a state of affairs about which you have knowledge). If I point to 100 people who had cancer, and 20 of them still have cancer, I can say that 80% of them have gone into remission. If I'm talking about percentages and probabilities of future events, more commonly called likelihood. These forms exists only in the mind. The alternative is to claim that the future exists but existence is a "now word." If you don't have access to information from something in principle, then it's safe to say it doesn't exist. Did Thomas Jefferson exist in the year 1400? If the future (and everything in it) exists then yes, because the 1700's were the future to the 1400's. Could you interact with him (in principle)? No. Which is more correct to say?

Whether or not people use "can" as some folk-definition of "possibility" when they say it, I suspect almost every single person uses "can" as "I see a way to get from State A to State B." This will necessarily ignore some or all of the reasons why the individual on the ground looking up at the apartment fire actually didn't get to State B, but the person simulating it in their mind can see it play out and believes it's possible or that the roadblocks to action were "overcomeable." Here's what I'm saying in code snippet form:

We don't blame a rock for rolling down a hill. It couldn't do otherwise. Isn't it unfair to blame people who couldn't do otherwise?

My position is that blame and praise are instrumentally valuable; yelling at a rock won't reduce future incidences of it taking or failing to take an action. Yelling at humans very well might. We can't be sure that blaming or praising a human will bring their desires in line with those of the one applying the social pressure. However, there's overwhelming statistical evidence that people who are expected to behave in a certain way (and where those expectations are backed by punishment or reward and blame or praise) are far more likely to behave in that way than those who don't. That makes blame and praise a rational thing to apply as the default position (if it were known that an individual were a sociopath or mentally damaged such that blame or praise had no effect, then it would be irrational to apply such methods).

Ok. So blaming people makes sense while blaming rocks doesn't even in the case that both lack contra-causal free will. That still doesn't restore "ought implies can." Applying blame to someone to fix future behaviors is still saying they ought to have done something different than what they did do. They couldn't have done otherwise without contra-causal free will. Therefore ought does not imply can.

Perhaps this is why free will advocates get so up in arms about blame and praise being incoherent in a deterministic world. Even if there are practical considerations for applying praise and blame, that one ought do something which they cannot flies in the face of intuition. How long should my prison sentence be for failing to stop the holocaust? Never mind that I wasn't even born when it happened. If ought doesn't imply can, most moral intuitions are out the window.

I propose that "ought implies can" is only false in a deterministic world where the word "can" is used as "ability." One doesn't have the ability to teleport matter. One doesn't have the ability to fly (without technology). One doesn't have the ability to decide to instantly be a great chess player (or "choose to win"). One doesn't have the ability to choose outside of the constraints reality places on them. In determinism, those constraints are absolute.

If "can" is used as "possible," then things change so long as one is honest about possibility. Possibility and probability exist in the mind - they are not part of the extra-agent territory of reality. If you have cancer you'll either get better or not. There's no "80% chance of remission" outside of your mind. That statement is an expression of the epistemological ignorance one has about all of the factors which will lead to one case or the other. If you were fully informed you'd either know what would happen or, if actual, REAL randomness exists (aka even reality doesn't "know" what it's going to do), knowledge would pretty much be impossible.

I'm not saying you can't point to mind-independent things and declare percentages, averages, etc. so long it references a past or current state of affairs (namely a state of affairs about which you have knowledge). If I point to 100 people who had cancer, and 20 of them still have cancer, I can say that 80% of them have gone into remission. If I'm talking about percentages and probabilities of future events, more commonly called likelihood. These forms exists only in the mind. The alternative is to claim that the future exists but existence is a "now word." If you don't have access to information from something in principle, then it's safe to say it doesn't exist. Did Thomas Jefferson exist in the year 1400? If the future (and everything in it) exists then yes, because the 1700's were the future to the 1400's. Could you interact with him (in principle)? No. Which is more correct to say?

Whether or not people use "can" as some folk-definition of "possibility" when they say it, I suspect almost every single person uses "can" as "I see a way to get from State A to State B." This will necessarily ignore some or all of the reasons why the individual on the ground looking up at the apartment fire actually didn't get to State B, but the person simulating it in their mind can see it play out and believes it's possible or that the roadblocks to action were "overcomeable." Here's what I'm saying in code snippet form:

void TryIt(int min)

{

if( min <= 0 || min > 0 )

{

stateA();

}

else

{

// will never be executed

stateB();

}

}

We'd say state B is impossible in the above due to a tautological if statement. Remove the tautology, however, ...

void TryIt(int min)

{

if( min > 0 )

{

stateA();

}

else

{

stateB();

}

}

... and we'd say stateB is possible because we see that, under certain conditions, stateB can be executed. However, it's easy to conflate possibility with "will actually happen." The revised snippet of code doesn't guarantee that stateB will be executed simply because this snippet of code doesn't contain all the factors which determine whether or not that will occur. The variable min connects this snippet of code to a larger scope of code which may be hidden from us.

Maybe there's something before control flows to this function that prevents the min variable from being less than or equal to zero. I would say that believing execution of stateB is possible in a "will occur" sense without understanding how min is constrained is a reflection of our ignorance, not a failure of the program's determinism.

There's a psychological phenomenon called correspondence bias. If we get mad and punch a wall it's because our boss is riding us and our dog is at the vets and we don't know how we're going to pay for it because our tax refund wasn't a big as we thought and, dammit, I'm not losing weight fast enough and do you think Kelly will return our call or was she just being nice when she took our number? If we see someone else punch a wall it's because "they're an angry person." The difference? We have mental access to (some of) the reasons leading up to the violent outburst. We don't have (as much) access to the reasons another might have done the same. The "computed can" is different.

We see what led us on the path from State A to State C and why we couldn't reach State B. When observing others, we don't factor those constraints in and say "if I were them, I could've done it" even though that statement is factually false - if you were them, you'd have all their dispositions, beliefs, and memories, causing you to behave the same as they did (or randomly if "quantum yadda yadda yadda").

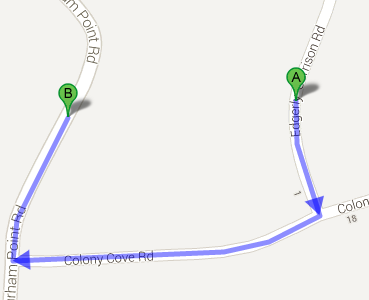

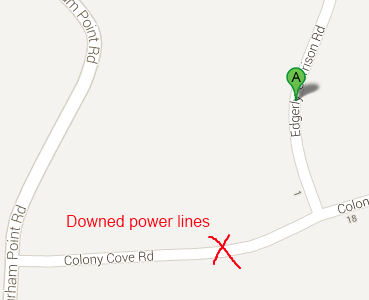

"Can" you drive from point A to point B? The epistemological versus the actuality.

Maybe there's something before control flows to this function that prevents the min variable from being less than or equal to zero. I would say that believing execution of stateB is possible in a "will occur" sense without understanding how min is constrained is a reflection of our ignorance, not a failure of the program's determinism.

There's a psychological phenomenon called correspondence bias. If we get mad and punch a wall it's because our boss is riding us and our dog is at the vets and we don't know how we're going to pay for it because our tax refund wasn't a big as we thought and, dammit, I'm not losing weight fast enough and do you think Kelly will return our call or was she just being nice when she took our number? If we see someone else punch a wall it's because "they're an angry person." The difference? We have mental access to (some of) the reasons leading up to the violent outburst. We don't have (as much) access to the reasons another might have done the same. The "computed can" is different.

We see what led us on the path from State A to State C and why we couldn't reach State B. When observing others, we don't factor those constraints in and say "if I were them, I could've done it" even though that statement is factually false - if you were them, you'd have all their dispositions, beliefs, and memories, causing you to behave the same as they did (or randomly if "quantum yadda yadda yadda").

"Can" you drive from point A to point B? The epistemological versus the actuality.

That you are believe driving from point A to point B is possible is a function of your ignorance of the downed power lines.

Our Old Friend Cost Makes an Appearance

Changing desires has a cost because changing physical underlying dispositions and aversions takes effort. Being informed has a cost because one must travel to where information can be intercepted or one must create proxies to capture it in their absence. There is also a cost to distill and formulate intercepted information into beliefs.

When someone blames a bystander for not running into the fire to attempt to save a child they are, in effect, saying that they could see how a person with "good desires" and true beliefs would actually run into the fire and attempt to save a child. Any dispositional roadblocks to that action that they do consider are seen as not important enough to justify letting harm come to a child through inaction. Blame and punishment are attempts to weaken or remove these dispositional roadblocks.

Our hypothetical bystander probably would not be blamed, unless perhaps he or she was the parent, guardian, or babysitter of the child. The disposition toward protecting one's own life is quite strong and very costly to weaken. The desires which seek to weaken such a disposition are far fewer and weaker than those which seek to promote such a desire.

People would almost assuredly use the word "reasonable" in making their case for whether or not the bystander should be blamed or punished. Reasonable (based on good sense) is a value-disguising term (what's good?) and values are inescapably tied to costs.

A more "reasonable" approach (cough cough) than There are less costly (as in thwarting desires) ways to prevent children from dying in fires than encouraging potentially sacrificing one's own life for that of a stranger in the rare circumstances where one would find themselves in an obvious position to do so. Better, less costly ways might include enhanced fire codes and a push for more smoke alarms and faster response times and more rigorous training from fire departments.

When someone blames a bystander for not running into the fire to attempt to save a child they are, in effect, saying that they could see how a person with "good desires" and true beliefs would actually run into the fire and attempt to save a child. Any dispositional roadblocks to that action that they do consider are seen as not important enough to justify letting harm come to a child through inaction. Blame and punishment are attempts to weaken or remove these dispositional roadblocks.

Our hypothetical bystander probably would not be blamed, unless perhaps he or she was the parent, guardian, or babysitter of the child. The disposition toward protecting one's own life is quite strong and very costly to weaken. The desires which seek to weaken such a disposition are far fewer and weaker than those which seek to promote such a desire.

People would almost assuredly use the word "reasonable" in making their case for whether or not the bystander should be blamed or punished. Reasonable (based on good sense) is a value-disguising term (what's good?) and values are inescapably tied to costs.

A more "reasonable" approach (cough cough) than There are less costly (as in thwarting desires) ways to prevent children from dying in fires than encouraging potentially sacrificing one's own life for that of a stranger in the rare circumstances where one would find themselves in an obvious position to do so. Better, less costly ways might include enhanced fire codes and a push for more smoke alarms and faster response times and more rigorous training from fire departments.

To Sum Up

- Ought implies can is intuitive.

- Ought implies can is practical - the incidents of "bad" states of affairs can't be changed through praise or blame, punishment or reward unless the individual against which such efforts are directed can actually influence reality in such a way as to reduce those incidents.

- Changing dispositions and aversions, and thus desires, has a cost. Strongly-ingrained dispositions, those which tend to aid in the fulfillment of other desires, and those which have many advocates will be more costly to weaken.

- Probability and possibility exist only in the mind, not in any extra-agent part of reality.

- Free will is not required for praise, blame, punishment, and reward to be instrumentally useful.

- Ought implies can still holds in a deterministic world so long as the word "can" is not used as a stand in for "ability" or "will."

* Without technology. Which you probably don't know how to make. And, if you did, maybe it'd be costly to do so or bulky to carry around. Some restrictions apply. Void where prohibited.