Why Elect People at All?

So, from the Segway, let's segue into politics. Why have elections at all? The problems are numerous and the primary benefit of getting the people to identify with the system can be had in other, much simpler and less problematic ways (though many including myself would question categorizing identification with a political system as a benefit). If people are going to make laws, why not have them be representative of the people they're to make laws for? The simple solution is sortition.

Representative Democracy

All three of these goals have failed to some degree in American politics. I want to focus on the representative goal for this discussion. There are two pertinent definitions of representative which I would like to address

2a : standing or acting for another especially through delegated authority

3 : serving as a typical or characteristic example

The primary process through which democracies enable the people to delegate authority to representatives is elections. This process is fraught with problems and workarounds which I'll address in later sections. I want to start with definition #3. There are general interests and specific interests. Having specific interests are fine so long as they are not enshrined in legislation at the expense of other groups. This is presumably why Rawlsians wouldn't want to limit the field of politicians to members of only one gender, race, occupation, or wealth bracket; specific groups of individuals will often have interests that aren't generally shared by those outside of the group.

If a certain group of individuals with certain common interests which aren't necessarily the general interests are represented far beyond their prevalence in the population at large, then how can the claim of representation of the public's interests be sustained?

Why So Many Lawyers?

- One who is versed in law has an advantage in making laws over one who doesn't

- Lawyers, on average, make more money than many other professions and campaigning is expensive

- Lawyering typically involves finding ways around things and talking to people, skills which are useful in politics

- Lawyers are likely to know some of the regulators, judges, and state prosecutors as part of their job - or know how to deal with them

I'm sure there are many more potential answers, but those are the four I want to focus on.

Hypothesis 1: Legal Expertise - Knowing the Procedural Game

In software engineering, libraries and standards are good until they stop working toward the goal of a product which satisfies the needs of users. There is no single best practice which is optimal in all situations.

Legislative and judicial matters rely far too much on what old, dead people said even if their justifications were faulty or no longer applicable. This is supposedly to build confidence in the institution of law, but I think it's largely laziness. You get people to have confidence in the law by having laws that make sense - laws that one doesn't have to break just to make a living or go about their day. There's too much reliance on "words of art" and seeing what sticks instead of what works. If laws had to pass by logicians or if they had to be compiled by a computer, I'm willing to be most of them would fall flat.

It's likely that I'm being unfair since I'm outside of both the legislative and lawyering professions. Still, I find it absurd to think that scientists and economists can't craft good policy if the point of that policy is to work. They may not honor the process but the process is only important in producing good laws (laws which a well-functioning society would use). I've already addressed arguments about undermining the law by not respecting the long-established traditions. So I dismiss those arguments. What's left? Not screwing people over for exigency? Yeah, that's part of a well-functioning society and part of establishing respect for the law so no problem their either. That's a process with a defined purpose relating to a well-functioning society, not a nod to tradition or compromise or keeping an old boys' club going.

Hypothesis 2: Campaigning is a Rich Person's Game

You'll never get money out of politics until you get power out of politics.

One of my solutions for the problem of monetary lobbying is localism. It won't get money out of politics entirely, but it will either reduce the influence of it or limit the extent of the damage it causes.

|

People become legislators because they either want to make the world a better place (as they define it) or because they want to make their own lives better without regard to others. The latter includes being drawn to power for its own sake.

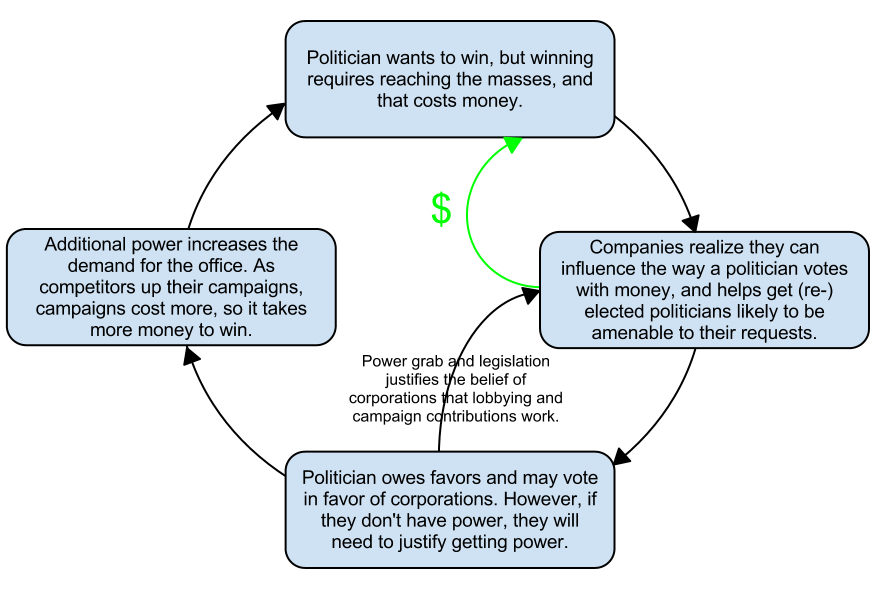

In both of those cases, the more power an office has the more attractive it is. For the beneficent planner, more power means more ability to effect the policy necessary to bring about their vision of a better society. For the purely self-interested, more power gives more ability to legislate towards one's interests. Presumably, the more power an office has, the more effort one will put into obtaining it. Money is the quickest route because one can leverage the efforts of others and spread a message with mass media. The need to campaign against others who are trying to get power leads to something approximating the positive feedback loop shown on the right. |

The solutions which actually work to break or weaken this feedback loop, unlike campaign contribution and political ad laws, are:

- Localism - cap power and you cap monetary influence and the number of individuals damaged by bad legislation

- Term limits - get money out of re-election. Keep the corporations guessing instead of betting on incumbents

- More choices - a first-past-the-post system favors two horses in the race. Having more potential winners spreads campaign contributions thinner.

- Eliminate elections altogether - at least at the higher levels - and that's the proposal here

Hypothesis 3: Political Overlap

Hypothesis 4: Good Old Boys

Random is a Crappy way to Figure Things Out ... Unless it's Better

|

A friend of a friend wrote Anywhere Tomorrow. In the earlier version of the manuscript I reviewed, there was a part of the story where people had to draw straws in a life or death manner. One of the characters pointed out (or thought, I forget) that relying on chance is a stupid way to decide things like that - in certain situations some people are more important than others. Presuming everyone shares the same goals (which, in that case, was survival) I completely agree.

Do politicians share general goals? Sure. Do individuals in positions of power have specific goals which work against the general interests of others? Sure. |

What sortition will get you?

- A value-free system of selecting individuals.

- An accurate cross-section of the population (a.k.a a representative sample); there's a reason research firms conduct random sampling. A legislature which cares about specific issues in proportion to how much the general population cares about them.

- No money to get people elected

- No incumbents or political dynasties

- Weaker political parties or political parties that focus on speaking directly with the people like they friggin' should.

- Less of a "my guy" attitude

- Less of a mental distinction between governors and non-governors

MOVE THIS ----vvv

If people generally share the same core values (murder, theft, assault are bad) then it's not like a pro-murder individual is very likely to be selected or, in the rare case they are, likely to be very effective at passing pro-murder legislation (presuming the constitutional aspect of The American Experiment is not an effective check).

Elections Make Use of Mind Hacks

Elections Cause People to Identify with Institutions

If I had to hazard a guess for why one is given legitimacy and the other not, I'd say it's because people erroneously believe that the government represents the people, is under the control of the people, and has the people's general interests at heart. With local governments this belief might be true, but at the national level it's pretty false.

Children are indoctrinated to respect authority and are given false civics lessons in school and people hold onto a romanticized notion of the great American experiment.

I don't mean to be critical of the people doing good work in government, even if bureaucracies tend to become corrupt over time. I'm critical of people giving passes to government that they wouldn't give to any amalgamation of individuals performing the same actions in the name of the social good.

|

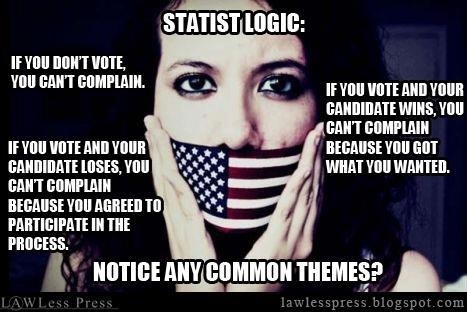

Elections are a primary cause of people giving passes to the institutions of government using the "rock-solid logic" listed to the right. But it goes further than denying people a justification for complaints - it enters The Most Dangerous Superstition territory; people believe in the system itself because it represents the will of people. It's not that they feel bad about complaining or doing something to remedy the existing problems in their lives or those introduced by government - it's that it honestly never occurs to them to do so.

Remove elections entirely and the "well that's the guy the people wanted" mentality disappears. More importantly, the "my guy" mentality either disappears entirely or is drastically reduced. I'd support sortition for this reason alone even if it provided no other benefits. |

Even the accidents of hereditary succession or of selection by lot, the plan of some of the ancient republics, may sometimes place the wise and just in power; but in a corrupt democracy the tendency is always to give power to the worst. Honesty and patriotism are weighted, and unscrupulousness commands success. The best gravitate to the bottom, the worst float to the top, and the vile will only be ousted by the viler. While as national character must gradually assimilate to the qualities that win power, and consequently respect, that demoralization of opinion goes on which in the long panorama of history we may see over and over again transmuting races of freemen into races of slaves.

As in England in the last century, when Parliament was but a close corporation of the aristocracy, a corrupt oligarchy clearly fenced off from the masses may exist without much effect on national character, because in that case power is associated in the popular mind with other things than corruption. But where there are no hereditary distinctions, and men are habitually seen to raise themselves by corrupt qualities from the lowest places to wealth and power, tolerance of these qualities finally becomes admiration. A corrupt democratic government must finally corrupt the people, and when a people become corrupt there is no resurrection. The life is gone, only the carcass remains; and it is left but for the plowshares of fate to bury it out of sight.

- Henry George, Progress and Poverty

|

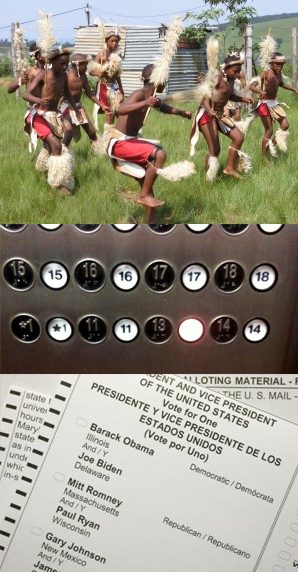

Beyond the corrupting influence, voting satiates a need for power in the masses. Substantive change won't happen by expending 15 minutes of effort every other year. That doesn't make you an involved citizen, it makes you a consumer picking from two carefully-packaged products. But it often removes an impetus for action because solving your own problems, or working in your community, or voting with your dollars is haaaaard. Filling out some ovals with a #2 pencil and stuffing them in a scantron is easy.

|

Rank the above in terms of effectiveness:

|