On Aspies : Why Taking Things to their Logical Conclusion isn't Usually Accepted

I'm writing this article primarily for libertarians who I count as my brothers and sisters. Libertarians tend to be overrepresented in the IT field. There are several possible reasons for this including having a career currently in high demand and believing that opportunities abound more than they actually do for people with skill sets less in demand.

I'm not going to go that route, I'm going to go another one - the IT crowd and libertarians hate compromises, special cases, and hard-coded values. The IT crowd tends to look for patterns from which to extract generalizations. While there may be a few considerations to balance, they're usually of a processing time versus memory versus development time nature and are fairly easy to optimize as compared to the much messier set of goals found in politics and society.

Trends can be misleading and any siren song preaching the right answer is to go 100% of the way leads many in the liberty movement to become ineffective change agents.

Common Examples

|

Statism

The state sucks for many reasons which libertarians, voluntaryists, and anarchists are not strangers to. A lot of my site is dedicated to pointing out how much the state sucks and, when it's not sucking, how dangerous it is to keep around - primarily for human actualization and the power process. Minarchists on reddit get derided for not taking voluntaryism to its logical conclusion and going anarcho-capitalist (though I've pointed out how that's not voluntary either). State sucks, get rid of the state. Simple, right? Especially when even minarchist states have slowly increased in scope until they become tyrannical. Well, except no large-scale (>150 person) anarchist society has survived without becoming a state or being conquered by a state while upholding an-cap principles. Humans kind of want their societies and ways of life to remain stable. While anarchy doesn't mean a bunch of competing warlords, that's how power vacuums play out in practice. Yes, there may be ways around some of the problems which caused failures in previous attempts, but a lack of examples makes people leery. That's not them being stupid, by the way, that's other values tugging against the liberty value and preventing the individual from valuing it totally at the sake of their other values. It's not inconsistent for them to stop at a point, even if it appears arbitrary; it's simply where the beliefs about the efficacy of a means towards actualizing two or more values combined with the relative strengths of those values are in balance.

|

Humans are subject to constantly competing fundamental dispositions.

There's no way to perform a one-time optimization among them for all situations. |

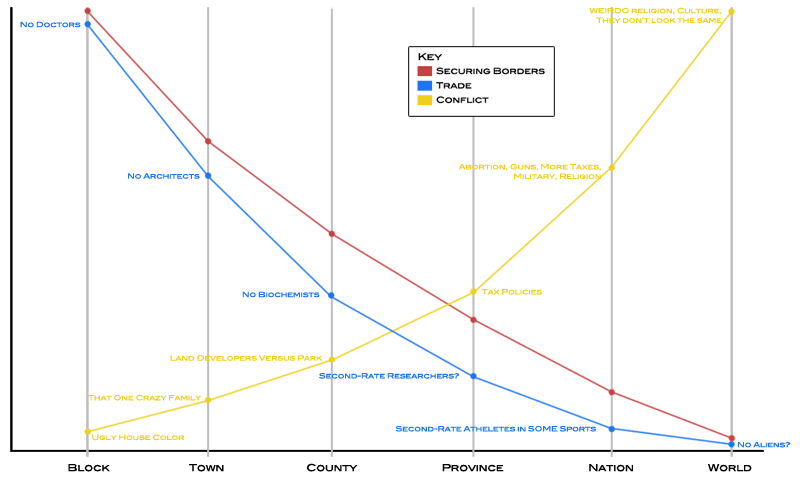

I was at a community meetup and someone was railing on about how we (the U.S.) should increase tariffs and prevent immigration to basically be protectionist. The anarchist in the group sarcastically asked "why stop there?" "Why not add tariffs and block immigration at the borders of each state? Or each town? Or each road?"

At the time, I agreed with his point that borders at the town level were equally as stupid as national borders because I dislike arbitrary impositions and interference with voluntary trade.

Revisiting it a few months later I realized that those borders might be artificial and arbitrary for me, but they are very real and non-arbitrary for others.

In many, the perceived benefits from liberty are countered by a desire for social cohesion through a sense of shared identity and values. Diversity is helpful if it's introduced slowly and in a measured way. Done too quickly or haphazardly it can easily destroy a society. Now, sure, those people can become part of a new society - but they don't want to.

The more locally you do things, the less you can do because you lack access to people with certain skills as well as certain climates and features of geography which make creating certain things possible. Blocking off a town from trade with the outside world would almost certainly destroy it. Blocking off the United States probably wouldn't because, so long as the need for foreign energy was addressed, there's not much that couldn't be made or grown in that area. There'd also be fewer people left outside who would be necessary. Experts on heart surgery or nuclear engineering are rare at a town level. At a national level, they are not that rare.

The shared history and sense of identity play roles too - especially language. Americans tend to think of themselves as American and that viewpoint has a lot of momentum. Even if the borders were initially unfounded, language and culture outside of those borders have changed enough that suddenly integrating with those other societies would likely be chaotic. That alone is reason enough for most to oppose making the borders more permeable or treating outsiders as part of the in group.

This is a progressive favorite and libertarians stupidly get roped in a lot of the time. The standard slippery-slope back and forth goes like this:

Progressive: "So why do you need an assault rifle?"

Libertarian: (If they're honest) "To resist tyranny."

Progressive: (Ignoring all history of guerrilla warfare) "That won't win against the U.S. government who have tanks and drones."

Libertarian: "It still will because in a war without a defined front insurgency works. Still, the point about parity of arms is well-taken. Doesn't it bother you that the state is trying to disarm citizens while increasing its own weapons technology?"

Progressive: "Oh, so you think you should be able to have an apache helicopter or a nuclear bomb?! Where do you draw the line?"

Yes, the logical endpoints are that nukes should either be allowed or disallowed or that arms should or should not be restricted. Balancing harm of malignant or incompetent use versus liberty to defend oneself versus the harm of not having an effective check on tyranny as well as the costs of expressing those values is what determines a widely-accepted reasonable stance on gun rights and restrictions.

As a geoist, this is one I get into often. First off, functional rights are whatever people are willing to respect. You can derive them however you want, but put a pound of derivation in one hand and a pound of shit in the other and see which fills up faster. Respect has costs. If things are easy to respect, they will be, if not, they won't be. It's really as simple as that no matter how much people hem and haw about it.

Negative rights tend to be easier to respect than positive rights because respecting them consumes less calories in general. If I have to earn money to send you to "free" college, then that's hard on me. If I have to not murder you, that's pretty easy.

With property, just about everyone can respect "property in one's person." Fewer, but most everyone can respect personal possessions. Fewer, but most everyone can respect someone's yard. Fewer still can respect absentee claims of land. Fewer still can respect claims over oil or fishing rights. Far fewer can respect claims over water. If any of those claimants are corporations, reduce the respect. If any are foreigners, reduce respect. If they are foreign corporations, really reduce the respect.

Exclusive use and claims might be necessary to make wealth and have stable, prosperous societies but it can reach a point where it actually undermines those goals and people simply can't afford to respect those claims. This is true both in the "starvation trumps idealism" sense where people aren't going to not trespass on land which they consider unused if the alternative is to be hungry or homeless. It's also true in the "loss of heritage" sense where people have aversions to degrade the sanctity of their society by privatizing things they identify with.

Effective Versus Efficient

|

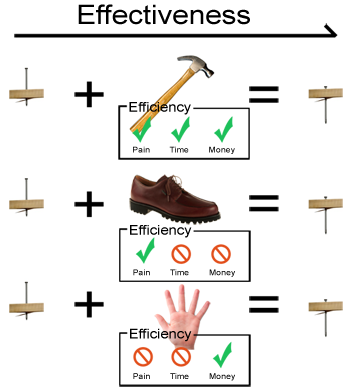

The above examples exemplify the distinction between effective and efficient.

Effective - Something is effective of some goal if employing it will cause that goal to become realized - can X cause Y? Efficient - Something is efficient if it doesn't cost too much of the other things one values - how much does X cost? An example I use to drive this distinction home is that of hammering in a nail. A hammer, a shoe, and your hand (depending on nail size and wood hardness) are all effective of that goal. The hammer is the only one of those three likely to be considered efficient. Using the shoe damages it and you likely have other goals for the shoe. Even if it's a junk shoe, it still takes longer and is probably harder to do. Doing things easily and in the least amount of time possible are general goals. Using your hand probably hurts and pain avoidance is generally a goal. Looking at means solely from a freedom (or any other value) perspective traps one into thinking in terms of effectiveness but not efficiency from the minds of other people who have goals you don't possess. Even if you can get people to agree to pound in a nail, you're going to have a hard time selling them on using their hands. That's the same structure as getting someone to admit there needs to be less government and then say "well, Blackwater (er Xe er Academi) can be the police" and "children and old people will be just fine... do I have proof? ... specific suggestions? ... meh, I'm sure it'll work." |

Not Being Aware of Others' Values Makes you Ineffective as a Change Agent

I got some personal insight into the “smart handicap” when I was a grad student. A friend and I were interested in taking an introductory course on the environment. What the heck: it would be a nice break from all-physics, all-the-time. Only we found out just before the beginning of the first class that it had been cancelled for the quarter. So we popped open the catalog, shopping for something else with which to entertain ourselves for the next hour, having already cleared the time. We spotted a course on Game Theory in the economics department, and minutes later walked into a dimly lit classroom of maybe 15 students sitting around a large U-shaped table. To illustrate one of the motivations for game theory, the professor pulled out a $20 bill and proposed a game to select a winner.

The game went like this: “Pick a number between 0 and 100. You’ll write down the answer on a sheet of paper and pass it forward. After you do so, I’ll take the average of the numbers and give the $20 bill to the person whose number is closest to one-half the average, so chose your number accordingly. Now go.”

I set about working my way through what would happen if people chose numbers randomly between 0 and 100, deciding that 25 would be the right answer in such a case. But wait, everybody’s probably thinking similar things. What if they all pick 25. Then 12 or 13 would be a good pick. But they’re right there with me, aren’t they? I should just go lower and lower. But wait, is everybody really pursuing this same line of thought? Are they second-guessing like I am? This is really a game about guessing how deeply others are thinking about it, or how deeply they judge the rest to be thinking about it. Oh heck; I’ll just put down 11 and be done with it.

There were some ridiculous guesses in the class. I recall that someone—no joke—picked 50. There might have even been a higher guess than this, but now it seems impossible that such a memory could be correct. There were a few 25′s and other guesses in that range. A few individuals picked zero, figuring that everyone would catch onto the downward convergence, and we could all split the money. They were incredulous when I won the $20 with my guess (and an outcome around 9, I believe). I recall that someone voiced utter disbelief that his zero wasn’t the correct answer.

Actually, I must admit that while I quickly understood the downward tug, I did not recognize until the game was over the beauty and perfection of zero as the only “right” answer. Lower numbers made me nervous, short-circuiting the theoretical pull to take the game to the extreme. This corrective impulse was apparently missing in the “smartest” students in the room, attracted as they were to the “perfect” answer.

- Do the Math on Crippling Intellects